The global response to COVID-19 has seen major advances in vaccine development. As the next step, pharmaceutical firms like Meiji Group are working to widen the range of available vaccine types.

While the COVID-19 pandemic continues unabated in parts of the world, mass vaccination programs have led to a dramatic reduction in hospitalization and mortality rates in many countries. However, not everyone is able to receive the vaccine made available to them, whether for health reasons or concerns about potential side-effects. Development of an inactivated vaccine, similar to the shots that already protect us from influenza and rabies, will increase vaccine choice and can help countries achieve near-total immunization.

How different vaccine types work

As a starting point, it's helpful to know the different approaches to vaccine development. As of November 2021, Japan has approved and is currently administering mRNA vaccines and viral vector vaccine for COVID-19. Both vaccine types contain instructions for making spike proteins, the mechanism by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus attaches itself to human cells. An mRNA vaccine uses messenger RNA, the genetic material that instructs the body on how to make spike proteins, while a viral vector vaccine delivers the spike protein DNA inside a different virus that is harmless to humans. In both cases, the immune system recognizes the new protein as a threat and develops antibodies to counter it.

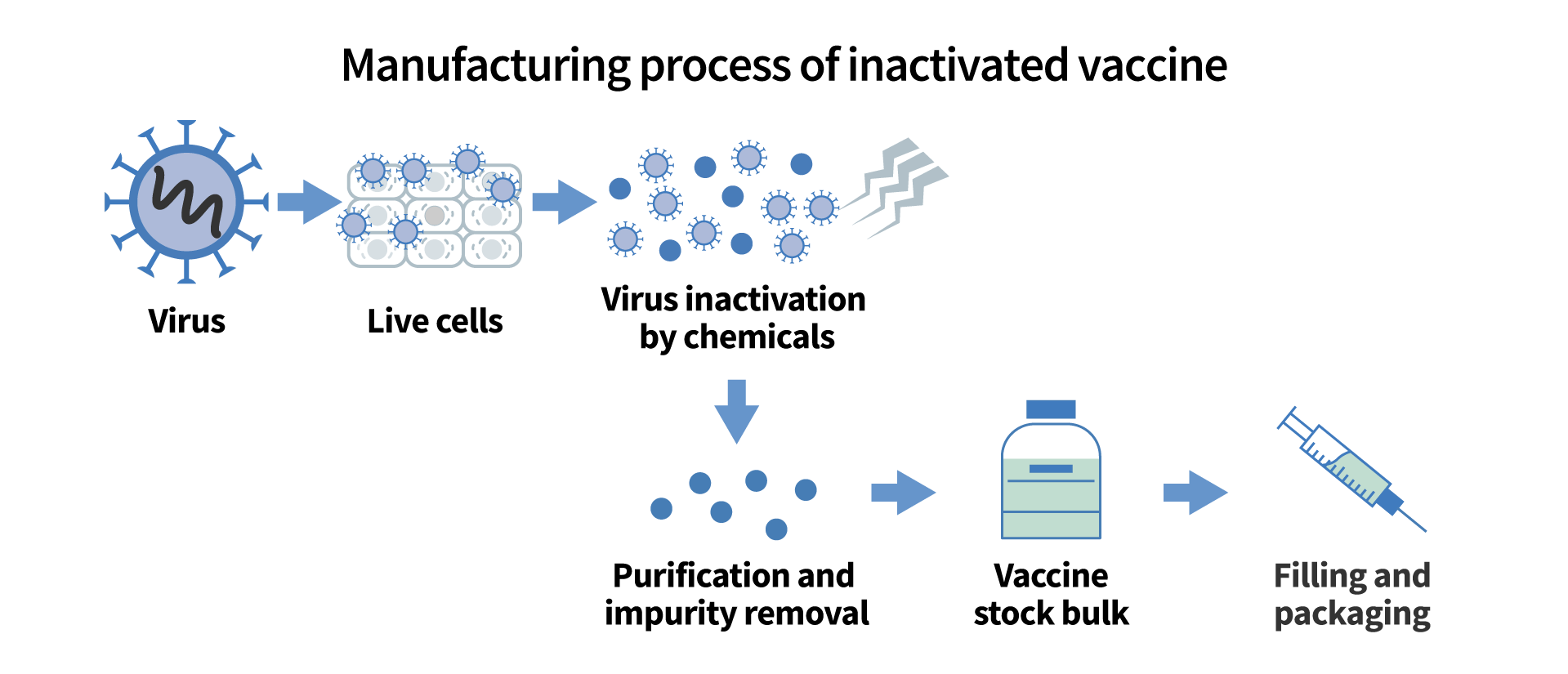

The pandemic has accelerated the development of these newer vaccine types, neither of which includes any trace of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. On the other hand, many conventional vaccines, like those in common use for influenza and polio, use a different process called inactivation. Inactivated vaccines generate an immunological response by introducing the virus itself to the body, but only after rendering it harmless using chemicals or heat. This is a well-established process and is considered safer than live or attenuated vaccines, which pose greater risks for the immuno-compromised.

The development of an inactivated vaccine would represent a milestone in the fight to bring COVID-19 under control. It will increase the availability of regular, seasonal jabs as societies learn to live with the new coronavirus. However, SARS-CoV-2 would need to be safely inactivated first. That process has been taken up by several research teams worldwide, including at Meiji Group company KM Biologics.

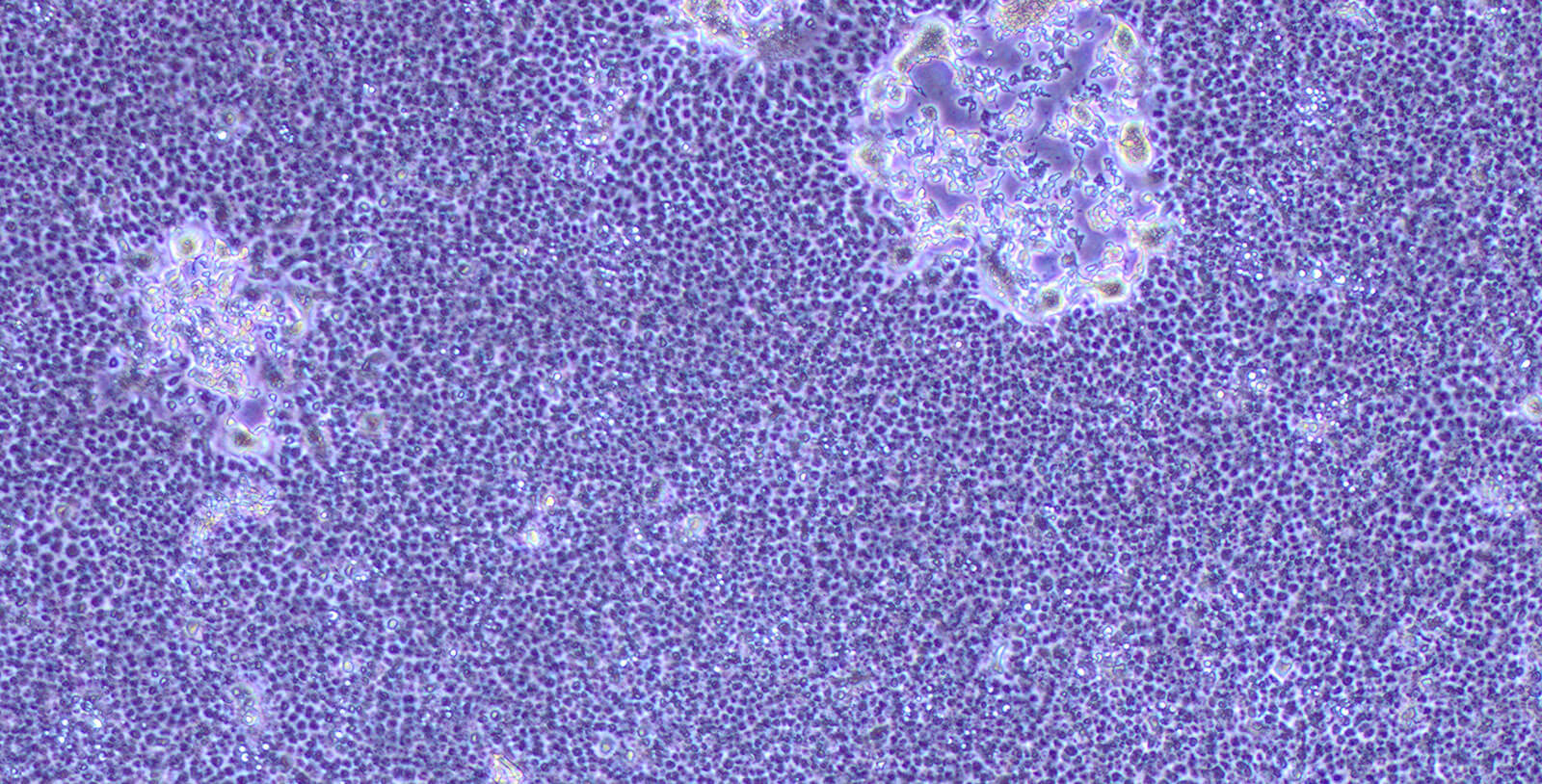

Cells infected by coronavirus and virus-denatured

Hope for an inactivated vaccine

Japanese biotech company KM Biologics has a history of vaccine development dating back to the 1940s, when it began production of a Pox vaccine in the aftermath of WWII. Since then, it has developed successful vaccines for influenza, rabies, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and Japanese encephalitis, among others.

Encevac, the company's Japanese encephalitis vaccine, makes use of Vero cells, a cell lineage derived from the extracted kidney of the African green monkey. Researchers found that Vero cells could also be used to produce the latest coronavirus, which would provide the basis for an inactivated vaccine. With facilities that can produce up to 57 million influenza vaccines, KM Biologics realized it had both the technological means and the production capacity to develop an inactivated vaccine for COVID-19.

The first step it took was to ensure the safety standards of its facilities. Safety at laboratories is rated on a BSL (biosafety level) scale of 1-4, with BSL4 the highest. Novel coronaviruses can only be handled at facilities rated BSL3, an extremely high level of containment. Since KM Biologics had already obtained BSL2+ certification, it was able to quickly set up BSL3 facilities before starting the development process.

The company is now cooperating with Japan's National Institute of Infectious Diseases, the University of Tokyo's Institute of Medical Science, and the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition to develop an inactivated vaccine for COVID-19. The project is being undertaken at unprecedented speed, with the first and second trial phases already complete. The initial target of commercialization in fiscal 2023 has since been moved forward to fiscal 2022.

"Development of an inactivated vaccine usually takes seven to ten years," says Sonoda. "This project, which aims to do so in about three years, is extremely unusual. Government support and quick decision-making from management are important, but the most important thing is the attitude of our researchers. Their desire to apply their professional skills to help the world break free from this pandemic is a major driving force."

The development process

Vero cells

Vaccination can help us live with coronaviruses

Human beings will almost certainly have to learn to live with COVID-19, which increases the need for ongoing vaccinations. For those concerned about possible adverse reactions, inactivated vaccines should provide greater peace of mind as they use methods proven to be safe and effective over many decades. Along with other antiviral drugs in development, they give patients and health officials a wider range of options to work with in the fight against COVID-19.

Scene from a clinical trial

"We can help to increase the vaccination rate in Japan by providing a new option for those who have not yet been vaccinated," says Sonoda. "Remember, smallpox is the only infectious disease caused by a virus that humans have actually been able to eradicate. So we can predict that new coronavirus infections will coexist with humanity, just like influenza, and vaccinations may be necessary on a regular basis. Inactivated vaccines, which have fewer adverse reactions, will almost certainly play an important role."